No industry likes any behavioural pattern that reduces their business scope. It is not a moral stance. It is not even a particularly human stance. It is simply the arithmetic of survival. When a pattern spreads that makes people need less of what an industry sells, the industry experiences the same feeling a cat has when it discovers the vacuum cleaner exists. It does not like it and it will behave accordingly.

Take retail; when consumers decided that waiting for a sale was preferable to buying at full price, entire sectors spent decades training people to feel that every price was already a gift from the shopping gods. When people started buying less and buying better, retailers invented loyalty programmes, limited editions and social pressure dressed as opportunity. The behaviour reduced scope so the industry responded by inventing new scope.

Consider fast food: when people became aware that eating something deep fried and salted until it became a structural material might not be optimal for health, the industry did not sigh and close the grills. Instead it created salads, wraps and a marketing language in which a salad comes with a motivational story and a wrap is described as an emotional journey. The behaviour threatened scope so the industry expanded the definition of what it could plausibly sell.

Finance offers a more subtle example; when customers learned that avoiding debt and living within their means improved their lives, the industry responded by inventing new products that made disciplined behaviour feel incomplete without a subscription. Rewards cards, premium accounts and investment apps became a way to monetize competence. Behaviour reduced scope so the industry reframed competence as a product.

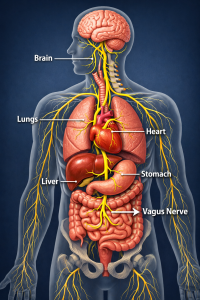

Healthcare is a more sensitive example because it deals with people rather than convenience. When people adopted preventative behaviour that genuinely reduced demand for certain treatments, whole new sectors grew around wellness, optimisation and longevity. The basic psychological reality is that when people stop needing a cure they often start wanting an enhancement. The industry follows the want when the need disappears.

Technology shows the pattern in its purest form. When users learned to uninstall apps, disable notifications and turn their phones into objects rather than companions, the industry created ecosystems that made stepping back feel like stepping out of society. New hardware, new services, new clouds and new subscriptions appear, not because people demanded them, but because the pattern of reduced engagement threatened scope.

The psychology underneath this is not sinister. It is simply shaped by three familiar forces:

Loss aversion is the first. People and organisations feel the pain of losing a market more strongly than the pleasure of gaining one. When behaviour threatens loss, creative energy becomes defensive creativity.

Incentive structures are the second. When a business is rewarded for selling more, it will invent reasons to sell more even when the original reason weakens.

The third is cognitive substitution. When an industry cannot directly defend its old scope, it substitutes a new meaning for the old behaviour. Eating becomes lifestyle, debt becomes empowerment, health becomes optimisation, communication becomes identity.

Humour helps because the pattern is almost gentle in its inevitability. You can watch an industry notice a behaviour that reduces demand and as if on cue it will produce a new category that sounds both helpful and vaguely like it should have been obvious years ago. You will hear things like premium water, artisan air, or personalised digital existence and you will feel a warmth of recognition.

The vacuum cleaner is back… watch out Kitty!!

References

Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow

Thaler, R. Misbehaving

Cialdini, R. Influence

Simon, H. Bounded Rationality

Ariely, D. Predictably Irrational