Given the amount of time we spend online, our digital environments are no longer background noise. They shape how we think, what we normalise, what we aspire to, and quietly, how we see ourselves.

We don’t just use the internet anymore; we live in it. Every feed, group, channel, and comment section is a room we walk into each day, and like any room, it has a tone, a culture, a set of unspoken rules. Spend enough time there, and those rules start to feel like reality.

This is why choosing who you follow matters more than most people realise. Platforms are built to amplify what holds attention. That often means extremes: certainty over nuance, speed over accuracy, confidence over competence. If your digital space is full of performative success, outrage cycles, relentless optimisation, or comparison masquerading as motivation, then that becomes the water you’re swimming in. You don’t have to consciously agree with it for it to affect you. Exposure alone is enough.

Over time, this shapes what you think is normal, what you think is possible, and what you think is wrong with you. That’s not a personal weakness; it’s environmental psychology.

In business spaces online, this effect is especially clear. There’s no shortage of “7-figure in 7 days” claims, recycled frameworks sold as revelations, and loud confidence with thin substance.

Spend long enough in those circles, and steady, ethical, long-term work starts to look slow or inadequate, and ordinary progress feels like failure. You begin to question your competence, even when your results are solid, not because anything is wrong, but because the comparison set is skewed. The humour here is that many of the loudest voices are selling courses about success rather than actually doing the work they describe. Your professional self-image is shaped less by your actual work and more by the digital room you sit in while doing it.

Outside of business, the same forces apply more quietly.

Feeds curate bodies, lifestyles, relationships, productivity levels, and emotional responses, all subtly edited, filtered, and optimised. The result isn’t usually dramatic distress; it’s something more mundane and persistent: mild dissatisfaction, background self-doubt, a sense of being behind without knowing behind what.

When your environment constantly signals what a “good life” looks like, it becomes easy to mistake curation for expectation. Mental health is not only about internal resilience. It’s also about external inputs. Online environments can increase cognitive load, reduce tolerance for ambiguity, encourage constant self-evaluation, and normalise anxiety as ambition. Even positive-sounding content can become corrosive if it implies constant self-improvement as a moral obligation.

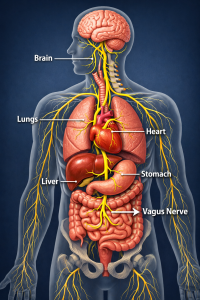

If you feel tired, flat, irritable, or quietly overwhelmed, it’s worth asking what you are repeatedly exposing your nervous system to. Not everything harmful feels hostile; some of it just feels busy.

This isn’t an argument for disengagement or digital minimalism as virtue. It’s about agency.

Choosing wisely means following people who think clearly, not just loudly, valuing depth over volume, noticing how content makes you feel after consumption rather than during, and allowing room for nuance, uncertainty, and ordinary human pace. A useful rule of thumb: if a space consistently leaves you feeling smaller, more rushed, or subtly inadequate, it’s shaping you whether you intend it to or not.

Offline, we intuitively understand this. We know that work cultures, friendships, and households influence us. Online, we often forget because the influence is fragmented, ambient, and always on. But the principle is the same. You don’t need to curate a perfect feed. You just need to be conscious that influence is happening.

Choose rooms that respect complexity, allow thinking, reward substance, and leave you clearer rather than noisier. Over time, those rooms don’t just inform your thinking; they shape your future.