Complaining feels harmless. It can even feel bonding. A shared eye roll in the office kitchen. A collective groan in the stands. A late night rant after a long day at work. For many of us, especially in high pressure environments, it feels like a release valve. But neuroscience tells a more interesting and less comfortable story.

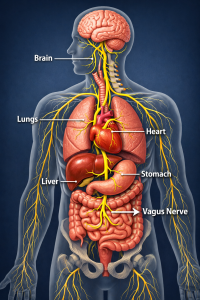

Research discussed by Stanford University School of Medicine highlights how repeated negative thinking patterns physically shape the brain. because it strengthens the circuits it uses most often through neuroplasticity. When we engage in chronic complaining, we repeatedly activate neural networks associated with threat detection and stress processing. Over time, the brain becomes more efficient at spotting problems, risks, and frustrations. In simple terms, the brain learns to look for what is wrong.

What begins as a temporary reaction becomes a default operating system. Not because someone is negative by nature, but because the brain has been trained to be that way. This has profound implications for business, leadership, teamwork, and even how we show up in our personal lives.

Complaining at Work: When Culture Shapes Cognition

In business environments, complaining often masquerades as realism. We call it being pragmatic, pressure testing or brain storming. In reality, when teams default to complaint driven conversations, they are potentially training collective attention toward threat, so it’s really important how these conversations are managed.

A meeting that opens with everything that will not work primes the nervous systems in the room for defensiveness. A manager who habitually vents about clients, leadership, or workload sets the emotional tone for the entire team. Over time, this creates a workplace where people scan for problems before possibilities.

The neuroscience matters here. As negative pathways become dominant, baseline stress increases. Emotional volatility rises. Small issues feel bigger than they are. Emails are read as criticism. Feedback is taken personally. Innovation slows because the brain, now oriented toward threat, prioritises safety over creativity. You will see it play out in familiar ways.

* A sales team that expects rejection starts to hear no before the prospect speaks.

* A project group spends more time protecting themselves than building solutions.

* High performers burn out not from workload alone, but from constant low level emotional strain.

None of this requires toxic leadership or dramatic conflict. It emerges quietly, reinforced one complaint at a time.

Leadership and the Amplifier Effect

Leaders need to be especially careful. Not because they must be relentlessly positive, but because their emotional habits are amplified. When a leader complains, it legitimises complaint. When a leader frames every challenge as an external threat, teams internalise that worldview. The brain, always learning, takes notes.

This does not mean ignoring problems. Effective leaders surface issues clearly, but they do so without feeding stress based narratives. They name the obstacle, then orient attention toward agency. The difference is subtle but powerful. One approach trains the brain to brace. The other trains the brain to respond.

Over time, teams led with the second approach show greater resilience, steadier performance under pressure, and lower emotional reactivity. This is not motivational language. It is neural conditioning.

Complaining in Personal Life: Emotional Muscle Memory

Outside work, the same mechanisms apply. When complaining becomes the primary way we process daily life, the brain becomes increasingly sensitive to inconvenience. Traffic feels personal. A delayed reply feels like rejection. Minor disruptions trigger disproportionate stress responses. This is why chronic complainers often feel exhausted without knowing why. Their nervous systems are constantly activated. The world feels sharper, louder, and more demanding than it really is.

The irony is that the more we complain to feel better, the more we reinforce the circuits that make us feel worse. Stanford’s discussion of affective neuroscience points out that awareness is the first step in redirecting these patterns. The brain remains plastic; it can change. But it changes based on what we repeatedly practise. That’s the key: attention is practice.

Sport, Supporters, and Shared Emotional Loops

Sport provides one of the clearest examples of collective neural conditioning. Fans who gather around shared complaint experience powerful bonding. Referees are biased. Management is clueless. The team always collapses under pressure. These narratives get repeated weekly, season after season.

Over time, supporters become conditioned to expect disappointment. Every mistake confirms the story. Every near miss reinforces the belief. The atmosphere shifts, tension rises faster. Enjoyment decreases even during success. The stress response becomes the default lens through which the game is experienced.

Yet teams with supporters who balance critique with belief create a different emotional environment. The brain, again, responds to repeated framing. Hope, patience, and perspective are learned responses just as much as frustration is. Here is what the ST rugby family is about: belief in the team despite everything.

Redirecting the Brain Without Pretending Everything Is Fine

This is not about forced positivity or silencing legitimate concerns. Complaints often contain useful information. The key difference lies in what follows the complaint.

? Do we stop at what is wrong, or do we move toward what is possible.

? Do we rehearse frustration, or do we rehearse response.

? Do we train the brain to detect threat, or to detect choice.

In business, this might look like structured problem solving instead of open ended venting. In personal life, it might mean noticing the impulse to complain and choosing a different frame. In teams, it might mean leaders modelling calm curiosity rather than emotional contagion.

These shifts feel small. Neurologically, they are anything but… Each redirection weakens old pathways and strengthens new ones. Over time, baseline stress reduces. Emotional volatility stabilises. The brain becomes better at resilience because it has practised it.

And Finally, A British Exception

All of that said, there is one category where neuroscience, leadership theory, and emotional regulation politely step aside: the weather. We Brits reserve the absolute right to complain about it. Rain when it should be sunny. Sun when it should be snowing. Heat that is somehow wrong. Cold that feels personal. This is not chronic negativity. It is cultural heritage. A social glue. A conversational warm up. A national pastime that harms no neural pathways and offends no productivity metrics.

Everything else, though, is worth paying attention to.

Because what we repeatedly focus on does not just shape our mood. It shapes our brain.