There’s a particular species that roams chat platforms, dating apps and even the dusty corners of WhatsApp groups. You’ve met them, I’ve met them and entire anthropological studies could be dedicated to them. Their defining feature isn’t charm, insight or evolutionary value. It’s the compulsive, unstoppable, gravitational-force-level need to have the last word.

You know the type. You politely decline a friend request, a chat, or the questionable privilege of being called “sweetie/hun/babe” by a stranger. You think the matter is resolved. It is not. Somewhere, a rejected male ego cracks like a glow stick and starts glowing neon green with the toxic urge to send one last message. And then another. And sometimes fourteen more. Each one intended to be the final one. Each one believing it has achieved conversational closure, only for the next one to pop up like a whack-a-mole in a leather jacket.

One of the most common versions is the classic “Fine. Whatever.” message. This is the last word attempt dressed in emotional armour, hoping to look unbothered while practically vibrating with botheredness. Immediately followed by the addendum message they claim they absolutely didn’t need to send but definitely did: “Just saying though, you didn’t have to be rude.” And a few minutes later: “But it’s cool.” And then: “Guess you’re not my type anyway.” Which, translated from the original language, means: Please validate me. Immediately.

There’s also the philosophical last-worder. The man who gets rejected and then suddenly becomes a TED Talk speaker in your inbox. You say “no thanks,” and he responds with a full-scale treatise on human connection, the nature of attraction and why women today don’t appreciate “real” men. You scroll three paragraphs down, and it turns into a manifesto about society. You didn’t ask for this seminar. It arrives anyway. Because he’s not the type to let the conversation die quietly. Oh no. He’s the type to conduct a post-mortem.

And then, of course, the silent last-worder. The typing indicator appears. Disappears. Appears again. Disappears. You can practically hear him wrestling with the perfect exit line, something that will both punish you and prove, beyond all doubt, that he was completely unaffected by your rejection. Eventually he settles on the timeless classic: “K.” A single letter. A single syllable. A single, fragile attempt to reclaim power. You can almost see him sitting back afterwards, arms folded, convinced he just delivered a Shakespearean soliloquy.

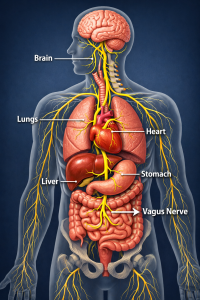

The psychology behind this is wonderfully predictable. Humans hate feeling dismissed. The ego hates it even more. And male ego combined with perceived rejection? It’s like adding Mentos to Diet Coke. The foam must escape somewhere, and usually that place is your inbox…

Last-word behaviour is basically a frantic attempt to rebalance the scales. If they get the last message in, they think they’re the one who ended things. They imagine themselves walking away in slow motion, sunglasses on, emotional explosions behind them, instead of you simply living your life on mute. Having the last word, to them, symbolises control. Narrative ownership. Dominance. In reality, it’s just digital flailing with punctuation.

What’s fascinating is that in everyday life this behaviour isn’t limited to dating apps. You see it in office emails where someone cc’s an entire department to prove they were right about printer settings. You see it in Facebook arguments where a middle-aged uncle refuses to let a thread die and ends up quoting articles from 2007. You see it in couples who have been together long enough to argue over who left the light on but still require a final remark like, “Well, I’m just saying, it wasn’t me.” Because even domestically, the last word is a trophy.

And yet the funniest thing about last-word enthusiasts is that they never actually get the last word. Because the true last word is always silence. Silence is the undefeated champion. Silence is the mic-drop. Silence is the universe closing the tab for you.

But try telling that to someone who is currently smashing out “GOOD LUCK WITH YOUR LIFE THEN” with the emotional stability of a caps-locking kettle. The last-word impulse is strong, ancient, primal. Some people hunt. Some gather. Some send one final message that says, “Just to clarify, I wasn’t even interested.”

It’s like we are not allowed to forget them. Mostly because they’ll keep reminding you.

References

Pennebaker, J. W. Linguistic patterns and emotional regulation in digital communication.

Baumeister, R. F. Self-esteem, ego maintenance and rejection responses.

Miller, G. The mating mind: how rejection scrambles communication behaviour.